Yet, if you ask locals of the older generation, you will be surprised at the different picture they paint about Port Dickson (a.k.a. PD). Several decades ago, it was common to see fishes darting amongst coral reefs in clear turquoise waters. Even my trip to the beaches in the 1990s revealed plenty of reef life. I could still recall those days I could easily find colourful flatworms, reef shells, porites corals, brain corals (Lobophylla sp.), carnation corals (Pectmia sp.), Acropora sp. corals and mushroom corals. And the water's visiblility is slightly above 2m. (That's considered rather good in the Straits of Malacca!)

Port Dickson is indeed a unique ecosystem in the Straits of Malacca as it is one of the few places in the straits where corals are able to establish themselves close to the mainland. In fact, this is arguably the only place in the west coast of Peninsular Malaysia with fringing corals. This is due to the fact that there are but two major river confluences with silty water flowing into PD's waters: The Sungai Linggi River in the South end and Kuala Lukut in the North. Conversely, the majority of the straits' coasts are sandy or muddy with mangroves for hundreds of miles. This is why PD is the place to go for Kuala Lumpur urbanites for a relaxing short trip for decades.

A typical scene in PD - fields of coral rubble stretching for miles along some beaches.

However, it's common sense to many that years of rapid and uncontrolled development and land reclamation works along the coast have all but reduced the corals to rubble. Silty waters covered most of the reefs and prevented life-giving sunlight from reaching the algae in the coral polyps, which they depend on to produce food to survive. With the daily onslaught of waves and rubbish scrapping on the reefs at high tide, there is little room for development of new coral colonies.

But after a diving trip at Lembeh Straits of North Sulawesi, Indonesia and exploring the reefs of Johore and Singapore Straits, I became aware that even environmentally degraded sites hold a surprisingly diverse ecosystem. With that in mind, I turned my attention to Port Dickson's corals. These few areas share plenty of similarities. They are busy ports, experiences rapid development and industrialisation and all have plenty of coral reefs in the vicinity. The only thing that sets them apart is that all of them are fed constantly by strong, nutrient rich currents while PD is pounded by silty, chemical laden concoction of seawater.

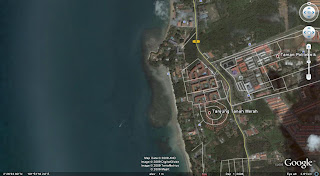

Nevertheless, an aerial survey of the coast reveals some surprising findings. PD's corals aren't all that lifeless after all:

But after a diving trip at Lembeh Straits of North Sulawesi, Indonesia and exploring the reefs of Johore and Singapore Straits, I became aware that even environmentally degraded sites hold a surprisingly diverse ecosystem. With that in mind, I turned my attention to Port Dickson's corals. These few areas share plenty of similarities. They are busy ports, experiences rapid development and industrialisation and all have plenty of coral reefs in the vicinity. The only thing that sets them apart is that all of them are fed constantly by strong, nutrient rich currents while PD is pounded by silty, chemical laden concoction of seawater.

Nevertheless, an aerial survey of the coast reveals some surprising findings. PD's corals aren't all that lifeless after all:

There are little corals left in the vicinity of the city centre at northern PD.

Some corals can still be seen on the islands and headlands off Kampung Si Rusa although they are either dead or almost destroyed by shoreline development activities.

The corals of Teluk Kemang are one of the more well-researched areas in Port Dickson.

Another well-developed fringing reef at Tanjung Tanah Merah.

Further south, fringing reefs can be seen stretching for several kilometres off Kampung Siginting and Guoman Hotel.

Tanjung Tuan or Cape Rachado is the most well preserved of all of PD's corals because it is gazeeted as a Permeanant Forest Reserve and therefore limits destruction of the marine denizens. However, lack of adequate patrols made it possible for some to encroach and exploit the fishes and corals for aquarium trade.

The patch reefs off Eagle Ranch Resort could be an interesting study area as they are located rather near to the silty mangrove shoreline on the mainland.

Some corals can still be seen on the islands and headlands off Kampung Si Rusa although they are either dead or almost destroyed by shoreline development activities.

The corals of Teluk Kemang are one of the more well-researched areas in Port Dickson.

Another well-developed fringing reef at Tanjung Tanah Merah.

Further south, fringing reefs can be seen stretching for several kilometres off Kampung Siginting and Guoman Hotel.

Tanjung Tuan or Cape Rachado is the most well preserved of all of PD's corals because it is gazeeted as a Permeanant Forest Reserve and therefore limits destruction of the marine denizens. However, lack of adequate patrols made it possible for some to encroach and exploit the fishes and corals for aquarium trade.

The patch reefs off Eagle Ranch Resort could be an interesting study area as they are located rather near to the silty mangrove shoreline on the mainland.

A few years ago, a friend of mine stumbled across a vast field of staghorn corals (Acropora sp.) several miles of Port Dickson on an exploratory dive trip; much like in Pulau Pangkor, Perak. So, there are corals that still survive in PD, divable or otherwise. But once again, the construction works on land will soon pull the plug for these poor creatures if nothing is done. More research and explorations has to be done immediately to better understand and manage the reefs.

Hopefully, some sort of protection will be given to these corals soon to avert the already growing danger of the collapse of the marine-related tourism industry and fisheries of the coast. Steps such as diverting sewerage waters from the sea to proper treatment plants and installing proper garbage disposal system should be considered. It is not too late to regain back what Port Dickson was once famous for - The Coral Reefs.

Some related links of interests:

1. New Strait Times-There's Still Hope For Port Dickson

2. Wild Singapore-Uniquely Singapore: City Reefs!

3. Wild Singapore- Sentosa: a shore doomed to reclaimation

4. Executive Summary EIA of a rest house in Pasir Panjang

5. The Star- Illegally Harvested Corals Seized

Reference and Further Readings:

1.Lau, C.M., and Affendi Y. A., and Chong, V.C. , (2009) Effect of Jetty Pillar Orientation on Scleractinian Corals. Malaysian Journal of Science, 28 (2). pp. 161-170. ISSN 13943065 (click here)

2.Sorokin, Y. I. (1993). Coral Reef Ecology. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

3.Titlyanov, E. A. (1981). Adaptation of reefbuilding corals to low light intensity. Proceedings of the Fourth International Coral Reef Symposium, 2, pp. 39-43. Manila.

4.Bhagooli, R., & Hidaka, M. (2004). Photoinhibition, bleaching susceptibility and mortality in two scleractinian corals, Platygyra ryukyuensis and Stylophora pistillata, in response to thermal and light stresses. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A, 137, pp. 547-555.

5.Obura, D. O. (1995). Environmental stress and life history strategies, a case study of corals and river sediment from Malindi, Kenya. PhD thesis, University of Miami,Miami.

6.Glynn, P. W. (1997). Bioerosion and Coral-Reef Growth: A Dynamic Balance. In C. Birkeland (Ed.), Life and Death of Coral Reefs (pp. 68-95). New York: Chapman and Hall. (click here)

7.Anthony, K. R., & Hoegh-Gulberg, O. (2003). Variation in coral photosynthesis, respiration and growth characteristics in contrasting light micro habitats:an analogue to plants in forest gaps and understoreys? Functional Ecology ,17, 246-159.

8.Lee, D. M. (2007). A comparative ecological study of the scleractinian corals (Porites rus) in Pulau Tioman and Port Dickson. Undergraduate Thesis, University of Malaya,Institute of Biological Sciences, Kuala Lumpur.

9.Brown, B. E. (1997). Disturbances to Reefs in Recent Times. In C. Birkeland (Ed.), Life and Death of Coral Reefs (pp. 354-379). New York: Chapman and Hall.

10.Yong, A. L. (2002). An ecological study of scleractinian coral in Tanjung Tuan, Port Dickson with regards to different light regimes. Undergraduate Thesis, University of Malaya, Institute of Biological Sciences, Kuala Lumpur.

11.. Hoegh-Guldberg, O. and Smith, G. J. (1989). The effect of sudden changes in temperature, light and salinity on the population density and export of zooxanthellae from the reef corals Stylophora pistillata (Esper) and Seriatopora hystrix (Dana). Journal of Experimental Marine Biology & Ecology (J.Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol.) 129: 279-303.

12.Westmacott S.K., K. Teleki, S. Wells, J. West. (2000). Management of bleached and

severely damaged coral reefs. IUCN, Gland Switzerland 37 pp.

13.Charles L Angell (2004) Review of critical habitats-mangroves and coral reefs. Final Report. BOBLME. (click here)

Hopefully, some sort of protection will be given to these corals soon to avert the already growing danger of the collapse of the marine-related tourism industry and fisheries of the coast. Steps such as diverting sewerage waters from the sea to proper treatment plants and installing proper garbage disposal system should be considered. It is not too late to regain back what Port Dickson was once famous for - The Coral Reefs.

Some related links of interests:

1. New Strait Times-There's Still Hope For Port Dickson

2. Wild Singapore-Uniquely Singapore: City Reefs!

3. Wild Singapore- Sentosa: a shore doomed to reclaimation

4. Executive Summary EIA of a rest house in Pasir Panjang

5. The Star- Illegally Harvested Corals Seized

Reference and Further Readings:

1.Lau, C.M., and Affendi Y. A., and Chong, V.C. , (2009) Effect of Jetty Pillar Orientation on Scleractinian Corals. Malaysian Journal of Science, 28 (2). pp. 161-170. ISSN 13943065 (click here)

2.Sorokin, Y. I. (1993). Coral Reef Ecology. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

3.Titlyanov, E. A. (1981). Adaptation of reefbuilding corals to low light intensity. Proceedings of the Fourth International Coral Reef Symposium, 2, pp. 39-43. Manila.

4.Bhagooli, R., & Hidaka, M. (2004). Photoinhibition, bleaching susceptibility and mortality in two scleractinian corals, Platygyra ryukyuensis and Stylophora pistillata, in response to thermal and light stresses. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A, 137, pp. 547-555.

5.Obura, D. O. (1995). Environmental stress and life history strategies, a case study of corals and river sediment from Malindi, Kenya. PhD thesis, University of Miami,Miami.

6.Glynn, P. W. (1997). Bioerosion and Coral-Reef Growth: A Dynamic Balance. In C. Birkeland (Ed.), Life and Death of Coral Reefs (pp. 68-95). New York: Chapman and Hall. (click here)

7.Anthony, K. R., & Hoegh-Gulberg, O. (2003). Variation in coral photosynthesis, respiration and growth characteristics in contrasting light micro habitats:an analogue to plants in forest gaps and understoreys? Functional Ecology ,17, 246-159.

8.Lee, D. M. (2007). A comparative ecological study of the scleractinian corals (Porites rus) in Pulau Tioman and Port Dickson. Undergraduate Thesis, University of Malaya,Institute of Biological Sciences, Kuala Lumpur.

9.Brown, B. E. (1997). Disturbances to Reefs in Recent Times. In C. Birkeland (Ed.), Life and Death of Coral Reefs (pp. 354-379). New York: Chapman and Hall.

10.Yong, A. L. (2002). An ecological study of scleractinian coral in Tanjung Tuan, Port Dickson with regards to different light regimes. Undergraduate Thesis, University of Malaya, Institute of Biological Sciences, Kuala Lumpur.

11.. Hoegh-Guldberg, O. and Smith, G. J. (1989). The effect of sudden changes in temperature, light and salinity on the population density and export of zooxanthellae from the reef corals Stylophora pistillata (Esper) and Seriatopora hystrix (Dana). Journal of Experimental Marine Biology & Ecology (J.Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol.) 129: 279-303.

12.Westmacott S.K., K. Teleki, S. Wells, J. West. (2000). Management of bleached and

severely damaged coral reefs. IUCN, Gland Switzerland 37 pp.

13.Charles L Angell (2004) Review of critical habitats-mangroves and coral reefs. Final Report. BOBLME. (click here)